1922

Hans Prinzhorn, “Introduction,” Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922; reprinted 1972)

The public has recently heard a great deal about “mad art,” the “art of the mentally ill,” “pathologic art,” and “art and insanity.” We are not overly happy with these expressions. The word “art” includes a value judgment within its fixed emotional connotations. It sets up a distinction between one class of created objects and another very similar one which is dismissed as “nonart.” The pictorial works with which this study is concerned and the problems they present are not measured according to their merits but instead are viewed psychologically. It therefore seems fitting to retain the significant, if not exactly common, expression “artistry of the mentally ill” for the title and for a subject which has so far been very little known outside of psychiatry. It includes all three-dimensional or surface creations with artistic meaning produced by the mentally ill.

Most reports published to date [1] about the works of the insane were intended only for psychiatrists and refer to a relatively few cases of the kind that every psychiatrist sees over a period of years. The studies of Mohr, [2] which are frequently quoted outside of technical literature, are notable for their exploration of more general problems, however. Unfortunately, there has never been a large collection of pictures which would provide, together with rich resources of comparative materials to minimize the danger of generalizing from too few accidentally discovered cases, the opportunity to investigate all kinds of interesting questions. Pictures by patients are probably known in every older mental institution. They have often been the occasion for the founding of small museums, or they have been added to already existing collections exhibiting figurines made from kneaded bread, escape tools, and casts of abnormal body parts; collections, in other words, very much like those which used to be made of curiosities….

We should say only this about the types and origins of our material: it consists almost exclusively of works by inmates of institutions – by men and women whose mental illness is not in doubt. Second, the works are spontaneous and arose out of the patients’ own inner needs without any kind of outside inspiration. Third, we are dealing primarily with patients who were untrained in drawing and painting; that is, they had received no instruction except during their school years. To summarize, the collection consists mainly of spontaneously created pictures by untrained mental patients.

[1] Most of the psychiatric publications are critically reviewed in Prinzhorn, “Das bildnerische Schaffen der Geisteskranken,” Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 52: 307-326, 1919.

[2] Mohr, “Über Zeichnungen von Geisteskranken und ihre diagnostische Verwertbarkeit,” Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie, vol. 8, 1906.

Excerpt source:

Hans Prinzhorn, “Introduction,” Artistry of the Mentally Ill: A Contribution to the Psychology and Psychopathology of Configuration, translated by Eric von Brockdorff from the Second German Edition (1922; reprint, New York, Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1972), 1-3.

1942

Alfred H. Barr, Jr., foreword to They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century (1942; reprinted 1999)

Each generation creates art. It also discovers art. It discovers art both of the more remote past and of the very recent past which we call the present….

Primitive is a term which has been stretched to include a great variety of art from Paleolithic sculpture to Alaskan totem poles, and from Italian “primitives” of the 13th century to the modern “primitives,” the “popular” or “self-taught” painters, which are the subject of this study. All this immense range of art has one extraordinary thing in common: it has been discovered esthetically and revalued within the past hundred years and mostly in the last fifty.

In fact it was just about fifty years ago that the greatest modern primitive, Henri Rousseau of France, was first given some appreciative recognition. Rousseau was not entirely self-taught but his psychological and pictorial innocence, his naïve realism and fantasy and his independence of tradition have made him the archetype of all painters of his kind. It is this last characteristic, independence of school or tradition, which distinguishes these painters psychologically and genetically from all other kinds of primitives, even from children who work in schools and often imitate each other. Their independence and isolation is revealed not only in their art but in their biographies so interestingly presented in this book.

Perhaps it is imprudent to try to evaluate the importance of the self-taught artists in comparison with other schools or kinds of living artists. Some of the painters in this book seem to me so obviously superior to others that I wish Mr. Janis had not been quite so generously inclusive. But it is by its finest artists that a school or movement should be judged and I for one think that, just as Rousseau now seems one of the foremost French painters of his generation, certain of our self-taught painters can hold their own in the company of their best professionally trained compatriots. Among 20th century American paintings I do not know a finer landscape than Joseph Pickett’s Manchester Valley, a more unforgettable animal picture than Hirshfield’s Tiger, a more original metaphysical composition than Sullivan’s Fourth Dimension, or a more moving portrait than John Kane’s painting of himself.

Excerpt source:

Alfred H. Barr, Jr., foreword to They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century (1942; reprint, New York: Hudson River Press and Sanford L. Smith and Associates, 1999).

1942

Sidney Janis, “They Taught Themselves,” chapter one in They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century(1942; reprinted 1999)

“Decline” in the Art of the People

It would appear from the studies already made in this field, that the tradition of art of the people, which flourished so profusely in America, reached an apotheosis in the second quarter of the 19th century and declined with the advent of a new era of science and industry. As the camera gained favor, the itinerant portrait painter, who had done the finest of this early self-taught work, was gradually eliminated from the scene. When the family album appeared on the table, ancestor paintings began to find their way to the attic, from the obscurity of which they were not to emerge until the second quarter of the 20th century….

In Search of a Name

The confusion caused by the various descriptive terms for self-taught artist leads one to ponder the problem of a name that will convey without ambiguity his place in the world of art. This problem is somewhat complicated by the fact that there are many categories of contemporary self-taught artists.

We find for example that Doriani paints humorous folk-art; Sullivan, whose work has the feeling of Mantegna, paints philosophical themes, while Hirshfield derives from psychological-instinctive sources. The New England landscapes of Moses, Southworth, Santo, Pa Hunt and Knapp are lyric and pictorial; those of Rev. Mulholland are spiritual in a religious sense. The direct approach, as it exists in child-art, is part of the elemental character of the work of Litwak, Crawford and Hutson. Church, the blacksmith, creates robust and Victorian fantasy, and the fantasy of Reyher springs from themes in poetry and the science of entomology.

These few examples demonstrate that there is a rich variety in the work of our contemporary self-taught artists, and it is important for this reason that a name be selected which is comprehensive enough to cover them all in one expressive category.

A variety of names has been used, none of them adequate. Some appear in this book because their specific gradations of meaning are effective. In the past, those most frequently used have been: Non-professionals, which is too general; Sunday Painters, affectionate but hardly accurate; Popular Painters, which suggests the popularity of song hits and Painters of the People, an agreeable name but too inclusive. The term Folk-artist implies a person who makes rural or peasant art and directs his efforts to objects made primarily for use. Instinctives they are, but they are very much more than this.

Naives, a name which in its purest meaning implies those who are artless, ingenuous, refreshingly innocent, may well apply. But unfortunately through common usage it calls to mind ignorance. Most frequently used is the term Primitives, which, although usage gives it a very wide application, is limited for our purpose. It may therefore seem that the combined term Naïve-Primitives most closely approximates the category under which these artists might be generally grouped. But besides being cumbersome, it still carries undesirable overtones.

The title, Self-taught Artists, which is favored by the author, adequately describes them, and is at the same time unassuming. While the definition as it stands might be stretched to include non-primitives, such as those who paint more or less academically, or even schooled artists who have rebelled against their schooling, there are apart from this, no implications to spoil its meaning. The term autodidactic, which André Breton suggests, comes even nearer an accurate description. But his is already associated with the sophisticated self-taught among the surrealist painters, who work with full knowledge of the tradition of art. Naïve-Primitive, then, is probably the most concise term, but Self-taught, which audience reaction also favors because of its close tie to everyday life, is used in the text as a more satisfactory one.

Sidney Janis, “They Taught Themselves,” chapter one in They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century (1942; reprint, New York: Hudson River Press and Sanford L. Smith and Associates, 1999) 4, 11-13.

1972

Roger Cardinal, “Cultural Conditioning,” Outsider Art (1972)

In his pamphlet, Asphyxiante culture, a classic statement of an anti-cultural attitude, the artist Jean Dubuffet relates an instructive anecdote to illustrate the degree to which cultural preconceptions can completely stifle the proper apprehension of anything that resists accepted ideas about art. It concerns a conversation he had with a teacher to whom he tried to expound the hypothesis that throughout history there have always been forms of art alien to established culture and which ipso facto have been neglected and finally lost without a trace. The teacher expressed his conviction that if such works had been assessed by contemporary experts and deemed unworthy of preservation, it was to be concluded that they could not have been of comparable value to the works of their time that had survived. To support this view, he cited the example of some German paintings he had seen in an exhibition. Though these had been executed at precisely the time the impressionist school was directing art into new channels, they bore no traces of that influence. After submitting these forgotten works to a thorough and objective perusal, the teacher felt obliged to admit that they were aesthetically inferior to the work of the impressionists; art criticism had accordingly been perfectly justified in preferring the latter.

Dubuffet points out the stupidity of this sort of reasoning, based as it is on a notion of objective value that betrays the worst kind of cultural myopia: where respected critics have testified their approval, there can be no dissension; bad marks in art can never be forgiven, at least not by layman. Dubuffet stresses the futility of the man’s ‘objective’ certainty, and suggests that it is only as a result of a particular education, of a particular cultural formation that the teacher made the judgement he did. His aesthetic preference was totally determined by these factors. A difference in his background or a difference in the opinion of the experts might well have led to a completely different assessment of the paintings concerned. Instead, the teacher bowed before the prevailing wind emitted by the Establishment, and could consent to find objective beauty only in the place marked out by a superior order.

Excerpt source:

Roger Cardinal, “Cultural Conditioning,” Outsider Art (London: Studio Vista and New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972), 7-8.

1976

Jean Dubuffet, foreword to Art Brut by Michel Thévoz (1976)

The consideration given to the work of professional artists has had the effect of conditioning the public, of creating a state of mind which makes it responsive only to the art displayed in museums and galleries or to art that depends on the same frame of reference, the same means of expression. Any works which, out of ignorance or obstinacy, depart from the accepted codes are given no more than a passing or condescending glance; or, at best, they are granted the status of a marginal art. Yet it may be that this is a misguided view. It may be that artistic creation, with all that it calls for in the way of free inventiveness, takes place at a higher pitch of tension in the nameless crowd of ordinary people than in the circles that think they have the monopoly of it. It may even be that art thrives in its healthiest form among these ordinary people, because practiced without applause or profit, for the maker’s own delight; and that the over-publicized activity of professionals produces merely a specious from of art, all too often watered down and doctored. If this were so, it is rather cultural art that should be described as marginal.

Excerpt source:

Jean Dubuffet, foreword to Art Brut, by Michel Thévoz (Geneva: Editions d’Art Albert Skira, 1976), 7.

1976

Michel Thévoz, “Prehistory of Art Brut,” in Art Brut (1976)

What is Art Brut? The by now standard French term was coined by Jean Dubuffet: it means “raw art.” Dubuffet not only created the notion, he also discovered and collected most of the works designated by this name. He has described them as “works of every kind – drawings, paintings, embroideries, carved or modeled figures, etc. – presenting a spontaneous, highly inventive character, as little beholden as possible to the ordinary run of art or to cultural conventions, the makers of them being obscure persons foreign to professional art circles.”[1] Again, in an essay entitled L’art brut préféré aux arts culturels, Dubuffet writes:”We mean by this the works executed by people untouched by artistic culture, works in which imitation – contrary to what occurs among intellectuals – has little or no part, so that their makers derive everything (subjects, choice of materials used, means of transposition, rhythms, ways of patterning, etc.) from their own resources and not from the conventions of classic art or the art that happens to be fashionable. Here we find art at its purest and crudest; we see it being wholly reinvented at every stage of the operation by its maker, acting entirely on his own. This, then, is art springing solely from its maker’s knack of invention and not, as always in cultural art, from his power of aping others or changing like a chameleon.”[2]

From these definitions, three essential features can be singled out. First, the makers of Art Brut are outsiders, mentally and/or socially. Second, their work is conceived and produced outside the field of “fine arts” in its usual sense as referring to the network of schools, galleries, museums, etc.; it is also conceived without any regard for the usual recipients of works of art, or indeed without regard for any recipient at all. Third, the subjects, techniques and systems of figuration have little connection with those handed down by tradition or current in the fashionable art of the day; they stem rather from personal invention. In short, Art Brut is opposed to what may be termed “cultural art,” including the avant-garde forms of the latter….

As regards the history of Art Brut and the creation of such works in the past, we are reduced to guesswork and conjecture, for very few of them have survived from before the twentieth century. This for an obvious reason; works of this kind went unnoticed and were not preserved. The fact is that Western society long remained blind to whatever departed drastically from its own standards, as fixed and institutionalized since the Renaissance. These standards found their strictest formulation in the academic canons. They were based on the exclusive priority of optical representation and all the conventions deriving from it. Thus painting was governed by the principles–necessarily arbitrary principles–of monocular vision, a fixed viewpoint, unity of time, space and lighting, planimetric projection, linear and aerial perspective, etc….

[1] Jean Dubuffet, Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, Vol. 1 (Paris: Gallimard, 1967).

[2] ibid.

Excerpt source:

Michel Thévoz, “Prehistory of Art Brut,” in Art Brut (Geneva: Editions d’Art Albert Skira, 1976), 9-10.

1989

John M. MacGregor, “Conclusion,” The Discovery of the Art of the Insane (1989)

The discovery of the art of the insane was not merely an intellectual operation. Twentieth-century artists in particular were challenged by this new art, and their own image-making activity changed in response to it. Certainly, the art of this century was influenced by the discovery of the art of the insane. The encounter of artists with this art, and their varying intellectual and pictorial responses to it, is part of the story of its discovery. Artists, unlike scientists, react by doing; discoveries are to be discerned most clearly in their work. In some cases it has been possible to point to clear pictorial evidence of influence from this source. But the primary influence of the art of the insane on modern art is to be found not in superficial formal similarities or coincidences of subject matter, but rather in the increasingly close proximity of these two forms of art, and in terms of the territory they both explore.

The absolute integrity and the pictorial strength that they saw in the work of the untrained insane encouraged many modern artists to risk opening up and giving expression to similar areas in themselves. Throughout the nineteenth century, and with vastly increasing speed in the twentieth, the subject matter of the artists becomes increasingly himself. Abandoning all outer pretext or rationalization, he sets out to explore his inner reality and to present it in images that are frequently utterly private and incomprehensible. This movement away from the surface was not the result of the artist’s contact with the art of the insane. As I have tried to demonstrate, the discovery of this new art form was merely an outcome of processes occurring in both art and psychiatry that were leading irresistibly toward the encounter with the unconscious.

Excerpt source:

John M. MacGregor, “Conclusion,” The Discovery of the Art of the Insane (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), 315.

1992

Maurice Tuchman, introduction to Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, exhibition catalogue by Maurice Tuchman and Carol S. Eliel (1992, Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The lineage of outsider-influenced modern artists in Parallel Visions [an exhibition that toured internationally in 1992-1993 and was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art] runs from Paul Klee to Gregory Amenoff. Klee’s interest in outsider productions can be traced to 1912, when, in a review of a Der blaue Reiter (The blue rider) exhibition, he urged the public to take the art of children and the mad seriously.[1] He also found confirmation of his own creations in the works collected by Dr. Hans Prinzhorn and reproduced in his book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the mentally ill), 1922, which was in circulation at the Bauhaus.[2] In these works Klee discerned “depth and power of expression….Really sublime art. Direct spiritual vision.”[3] …

Decades after Dubuffet’s ground-breaking assertion that art brut was to be preferred over the cultural arts, Roger Cardinal sought to further define art brut and settled on the term outsider art for his book published in 1972.[4] In a letter to Seymour Rosen, Cardinal recounted his odyssey in search of usable terminology:

Many terms have been used which allude to the creator’s social or mental status – isolate art, maverick art, outsider art, folk art, visionary art, inspired art, schizophrenic art. This seems unsatisfactory in as much as not every creator we want to recognize fits so readily into a social or psychological category. I feel strongly that to label works in a way that stresses the eccentricity or oddness of their maker tends to divert attention from aesthetic impact onto the biographies….”

[1] Paul Klee, Diaries of Paul Klee, 1898-1918 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964), 266.

[2] Hans Prinzhorn, Bildnerie der Geisteskranken (Berlin: Springer, 1922; reprint, Berlin: Springer, 1968). Published in English as Artistry of the Mentally Ill: A Contribution to the Psychology and Psychopathology of Configuration, trans. Eric von Brockdorff (New York: Springer, 1972).

[3] Felix Klee, Paul Klee (New York: Braziller, 1962), 183.

[4] Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art, (New York: Praeger, 1972), 9.

Excerpt source:

Maurice Tuchman, introduction to Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, exhibition catalogue by Maurice Tuchman and Carol S. Eliel (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Princeton University Press, 1992), 11.

1993

Driven To Create: The Anthony Petullo Collection of Self-Taught & Outsider Art – A European Anthology by Roger Cardinal – Milwaukee Art Museum (1993)

Essay by Roger Cardinal

1999

Alfred M. Fischer, “Looking at Bill Traylor: Observations on the Recepetion of his Work,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues (1999)

Without doubt, Traylor, who worked his whole life, viewed his drawing activity as a type of handicraft; Shannon’s [Charles Shannon, who befriended Traylor in 1939] observation that Traylor gradually came to believe he was working for him confirms this. On a fence behind his “workplace” on the open street he strung up his drawings to sell them to passers-by. “Sometimes they buys ’em when they don’t even need ’em,” he said to Shannon amused.[1] The statement indicates that he had no conception of the “autonomous work of art.” When Shannon was asked once whether Traylor knew that he [Shannon] was an artist, he replied: “I really don’t know. I don’t remember telling him that I was.”[2] Shannon certainly assumed that Traylor was unable to understand the notion of identifying oneself as an artist. Indeed, he seems to have attempted to guard him against such thoughts.[3]…

By definition, “folk art” serves the needs of everyday life, and surely Traylor understood his drawings in this sense. For the most part the customs, traditions, practices and habits of African Americans determine the nature of his drawings; and the expressiveness of their songs, dances and stories is rendered pictorially in Traylor’s work. In like manner his work can be placed within the realm of naive art, in so far as pictorial conception and reality become one: like children or tribal people, Traylor does not differentiate between image and lived experience. In his work there does not appear to be any taking issue, searching for meaning, questioning or problem solving; instead he “only” depicts what he has experienced, seen and heard, with unabashed high spirits and zest for living. The sincerity, unaffectedness and authenticity with which he does this are, of course, exactly the characteristics which the modernist artists could only emulate in their own works.

[1] Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco, Bill Traylor: His Art, His Life (New York: Knopf, 1991), 8.

[2] Ibid, 15.

[3] According to Cameron (Dan Cameron, “History and Bill Traylor” in Arts Magazine 60, no. 2, 1985, p. 46), Shannon “intentionally shielded” him (“for fear of breaking the spell”).

Excerpt source:

Alfred M. Fischer, “Looking at Bill Traylor: Observations on the Recepetion of his Work,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues, edited by Josef Helfenstein and Roman Kurzmeyer (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999) 163-164.

1999

Josef Helfenstein, “Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon: A Historic Encounter in Montgomery,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues (1999)

At the sight of Traylor absorbed in his work, Shannon [Charles Shannon, who befriended Traylor in 1939] witnessed a process that profoundly fascinated him: he saw how a person who could not even write and had never drawn or painted discovered the secret of visual creation through the possibilities of the line.[1] In the days and weeks that followed, he observed how Traylor, in a phase of unceasing productivity, came to terms artistically with his past life and the things he saw around him. “Drawing became Traylor’s life. He worked all day; some evenings I would drop by around ten o’clock and he would still be there, his drawing board in his lap, a brush in his hand. He was calm and right with himself, beautiful to see.”[2]

[1] Charles Shannon, “Bill Traylor’s Triumph,” in Art and Antiques, February 1988, p. 88.

[2] Ibid, 62.

Excerpt source:

Josef Helfenstein, “Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon: A Historic Encounter in Montgomery,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues, edited by Josef Helfenstein and Roman Kurzmeyer (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999) 99.

1999

Matthew Gale, “Artistry, Authenticity and the Work of James Dixon and Alfred Wallis” in Two Painters: Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, exhibition catalogue (1999)

… The encounters between artists and primitives resulted in an unlearning of conventions by the trained in the face of these personal views of reality, independently expressed. In essence, this reflected the prevailing concerns and currents of industrialized society, which ensured that authenticity was valued over artistry. The apparent simplicity of this value system belies the complexity of the relationship born of encounters between professional artists and such painters as Alfred Wallis and James Dixon. Aspects of these relationships between the participants will be examined here.

So seductive was the call of the simple life that a number of artists sought to become ‘primitive’ themselves. The example of Paul Gauguin is often cited, although his primitivizing art is recognizably based on a whole swath of learned sources. In the twentieth century there were also artists within the mainstream of Modernism – such as Marc Chagall – whose work was at various times considered primitive. Christopher Wood is another of these, as his painting is often described as Naïve. This exposes the inadequacy of the terms, as he (who trained briefly as an architect and was encouraged to study art in Paris by Augustus John and Alphonse Kahn) and Wallis (the retired rag-and-bone dealer from St. Ives) clearly enjoyed different circumstances. It is telling how the badge of untrained artist was proudly worn by professionals, reflecting the view of art education as a crushing weight. It was in these circumstances that the search for authenticity was undertaken….

The promotion of Rousseau’s work by avant-garde artists before and after his death in 1910 is echoed in comparable situations across the Western world.[1] Thus, when Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood ‘discovered’ Wallis in 1928, and Derek Hill ‘discovered’ Dixon around 1960, all were participating in a well-established pattern. Its repetition across the years exposes these discoveries as, in effect, meaning ‘introduced into the system’. The Modernists brought the primitives to a wider public by establishing the climate for the acceptance of such work. Whether or not they stood to gain materially, the Modernists established their association with this raw creativity.

[1] See Kenneth Coutts-Smith, “Some General Observations on the Problem of Cultural Colonialism,” (1976; reprint London and New York: Routledge, 1991).

Excerpt source:

Matthew Gale, “Artistry, Authenticity and the Work of James Dixon and Alfred Wallis” in Two Painters: Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, exhibition catalogue (London: Merrell Holberton Publishers Limited in association with Irish Museum of Modern Art and Tate Gallery St. Ives, 1999) 16-17.

1999

Roman Kurzmeyer, “Plow and Pencil,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues, edited by Josef Helfenstein and Roman Kurzmeyer (1999)

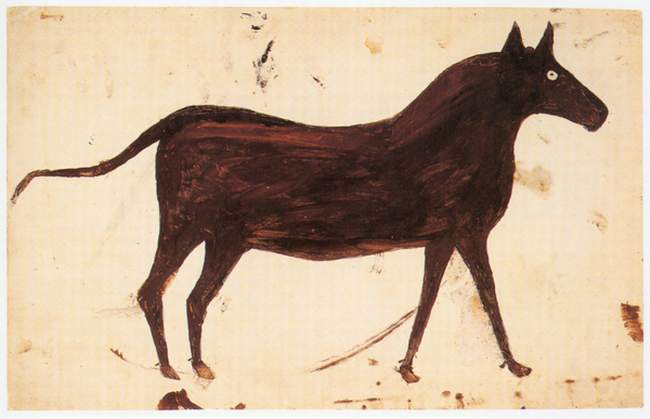

Brown Mule, 1939

Pencil, crayon, and gouache on board

American

With his activity in Montgomery [Alabama], Bill Traylor pursued neither an artistic career nor a particular social agenda. Why he began to draw is unknown, and it remains uncertain whether he even conceived of himself as an artist. When he came to Montgomery, he left the extended family among whom he had lived even into old age. No role models were available for his new activity; his personal history and social origin provide no explanation for his beginning to draw. The road Bill Traylor traveled when he came to Montgomery from Church Hill and took up his pencil cannot be measured in miles. In the eyes of his contemporaries, he was not the artist we now consider him to be. Even the few articles written about him during his lifetime – one of them published in the June 22, 1946 issue of the widely-circulated magazine Collier’s – and the two exhibitions in Montgomery in 1940 and Riverdale near New York in 1942 cannot obscure this fact. When he died in 1949, his life story had not yet been written….

The history of the reception of Traylor’s art shows that as knowledge of the circumstances of his life has increased, the understanding of his work had gradually changed as well. Although Bill Traylor was underprivileged, homeless, poor, old, and infirm, traces of a secret grudge are nowhere apparent in his work. A certain distance to his own fate gave his drawings a unique wit and freedom of expression, but also an element of black humor. The story of Bill Traylor’s life does not explain why he began to draw, but it may help to account for the simplicity of his drawings and his interest in the house, in pulsating lines and breathing planes: his work reflects a deeply rural conception of life….

After the death of Bill Traylor, Charles Shannon possessed 1200 to 1500 of his drawings from the years 1939-1942; for lack of outside interest, however, he laid them aside. Shannon’s resignation was well-founded: abstract art had conquered New York and assumed its peculiarly American form in the Abstract Expressionism of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Philip Guton, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman.[1] During the years of the New Deal, Social Realism had represented the dominant artistic style, and in the period before the war social-political involvement was taken for granted among artists and intellectuals. At that time the notion of a genuinely American art was widespread and would hardly have been foreign to Charles Shannon. His enthusiasm for Bill Traylor should be interpreted not least of all in this context. When Charles Shannon returned from the war in 1946, however, he not only found a different society, but also observed how within a few years a new concept of art prevailed in the form of Abstract Expressionism, a movement with international aspirations. Decades passed, and the drawings by Bill Traylor were apparently forgotten.

It was the interest of his wife Eugenia Carter Shannon that inspired Charles Shannon to revive the memory of his old friend Bill Traylor in the 1970s….Finally, the breakthrough occurred when works by Bill Traylor were shown in the exhibition Black Folk Art in American 1930-1980 in 1982 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

[1] See Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

Excerpt source:

Roman Kurzmeyer, “Plow and Pencil,” in Bill Traylor 1854-1949: Deep Blues, edited by Josef Helfenstein and Roman Kurzmeyer (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999) 11.

1999

Sarah Glennie and Michael Tooby, foreword in Two Painters: Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, exhibition catalogue (1999)

As the emphasis in art turned away from imitation towards expression during the twentieth century, the work of untrained or ‘primitive’ artists became an important influence for Modernist painters and was actively sought out. Artists looked for a directness and purity of expression in the work of untrained artists and celebrated the apparent lack of decision-making or analysis in the work. For example, Picasso and Braque looked to the work of Henri ‘le Douanier’ Rousseau in France at the beginning of the century, and later Dubuffet actively collect ‘L’Art Brut’ or ‘Outsider’ art. Ben Nicholson once remarked of Alfred Wallis, “One finds the influences one is looking for.”

Excerpt source:

Sarah Glennie and Michael Tooby, foreword in Two Painters: Works by Alfred Wallis and James Dixon, exhibition catalogue (London: Merrell Holberton Publishers Limited in association with Irish Museum of Modern Art and Tate Gallery St. Ives, 1999)) 6-7.

Port St. Ives, c. 1939

Oil and pencil on cardboard

British

2000

Colin Rhodes, “Other Positions,” (2000)

Populations inevitably look first to themselves for cultural sustenance, but a shared sense of self-identity can be challenged by the recognition of difference in others even within small cultural units. Recognition of difference — at even the most primitive level between the ‘self’ and the ‘object’ — is controlled by our projection of ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’ onto the Other. The American writer Sander L. Gilman has argued that our common tendency to create stereotypes arises out of a basic human need to cope with ‘anxieties engendered by our inability to control the world’. Encounters with Otherness result in the construction of stereotypes that operate as a means of perpetuating a sense of self-identity. However, the illusory line we draw between self and the Other is a shifting one, adjusted according to changes in our perceptions. As Gilman says, ‘paradigm shifts in our mental representations of the world can and do occur. We can move from fearing to glorifying the Other. We can move from loving to hating. The most negative stereotypes always have an overtly positive counterweight.’ At the heart of this, though, lies the recognition of difference and the projection of value judgments into its identification. Historical encounters of imperialist cultures with Otherness and their aftermath offer clear examples not only of the dynamic nature of stereotypes, but also of their essentially mythic nature.

Excerpt source:

Colin Rhodes, “Other Positions,” (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2000), 198.

2000

Jane Kallir, “European Self-Taught Art: Brut or Naïve?” (Galerie St. Etienne, 2000)

Self-taught art has been an important adjunct to the contemporary art scene for roughly one hundred years. Yet, though the field (as distinct from the art itself) originated in Europe, its American component has frequently been viewed in isolation. The term “Outsider art” was initially intended to be the English-language equivalent of European Art Brut, but American Outsider art — with its quirky mix of folk objects, environments, amateur paintings, works by the mentally ill, ethnic expressions and religious proselytizing — at times differs markedly from Art Brut. Indeed, surprisingly few American collectors of the native product have much awareness of the genre’s European antecedents….

The field of self-taught art was constructed in early twentieth-century Europe as an alternative to a civilization perceived to be in irreversible decline. However, unlike the other kindred modernist movements, such as Fauvism, Cubism and Expressionism that arose around the same time, self-taught art allowed for practically no input from the creators themselves. In fact, the creators were elected by virtue of their distance from the self-conscious art world, which projected onto those creators’ ideals that often could not be met. The myth of absolute originality was shaken every time it was revealed that a self-taught artist had been influenced by an outside source. The myth of purity crumbled almost as soon as an artist was discovered and taken inot the evil commercial marketplace. Convinced that the hypothetical tree falling in an empty forest does make a noise, the art world set out on an impossible mission to record the sound.

The first self-taught artist to be anointed by the art world was the French toll-collector Henri Rousseau. Discovered in the early years of the twentieth century, he was the original “Naive,” and much was made of his supposedly gullible, childlike character. (Rousseau’s “gullibility” actually consisted primarily of being foolish enough to take himself seriously as an artist.) Other discoveries in the Naive mode quickly followed after Rousseau’s, particularly in the period between the two world wars when modernism began to develop wider international recognition. Both in Europe and the United States, these first-generation Naives were relatively conventional picture-makers. Denied formal training due chiefly to economic circumstances (or, particularly in America, geographical remoteness), these painters nonetheless pursued goals shaped by the traditional academic genres of landscape, portraiture, and still life. Their originality lay in the ad-hoc methods the artists invented to achieve these goals, drawing on whatever visual sources they could muster and combining those sources with direct observation and trial-and-error experience. If Art Brut and Outsider artists tend to look inward (depicting the “private worlds” referenced in the Katonah exhibition title), the Naives looked outward, reflecting a more public, generally accessible view of their surroundings.

Alongside the Naive movement, another related but distinctly different phenomenon was quietly developing. In 1921, Walter Morgenthaler published his monograph on Adolf Wölfli, A Mentally Ill Person as an Artist. And in 1922, after a marathon three-year collecting spree, Hans Prinzhorn issued his landmark survey, The Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Both authors were psychiatrists who had initially encountered their subjects in clinical settings, but they broke new ground in recognizing that the work of the mentally ill could also be appreciated as art. Unlike Naive art, which in the interwar period was finding its way into galleries, museums and private collections, partly aided by the artists themselves, the art of the mentally ill remained largely the province of a few specialized connoisseurs. Such art was too difficult to attract a wide public at this time, and hospitalized artists were for the most part unavailable or unable to engage in self-promotion. However, the Morgenthaler and Prinzhorn books did reach the right people. A number of German Expressionists made pilgrimages to the Prinzhorn collection at the University of Heidelberg’s Psychiatric Clinic, and Prinzhorn’s book became the “Bible” of the French Surrealists.

Undoubtedly, Freud’s reification of the unconscious and his seminal work on dreams contributed substantially to the surge of interest in the art of the mentally ill that developed after World War I. In the ensuing decades, this interest continued to percolate through the European health-care and artistic communities, which worked in tandem to preserve and celebrate psychiatric art. Indeed, the persistant intertwining of these two intellectual communities is one of the chief characteristics that distinguishes the development of European Art Brut from American Outsider art. Following Prinzhorn’s lead, the Royal Bethlem Hospital in Kent, England, the Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris and, more recently, the Lower Austrian Psychiatric Hospital in Gugging and the Hospital Art Center — La Tinaia in Florence, Italy, all developed various kinds of programs revolving around artist-patients. Among the mainstream artists who drew inspiration from these psychiatric programs during the postwar period were Arnulf Rainer in Austria and, above all, Jean Dubuffet in France.

By the late 1940s, when Dubuffet began his efforts in earnest, the prewar European avant-garde was establishing itself as a new “academy,” and the Naives whom these artists had once fostered, with their comforting landscapes and idiosyncratic but endearing portraits, were welcomed warmly by a public chafing against the ascendancy of abstraction. It grew increasingly difficult to distinguish read from faux Naives, as the style became a staple of greeting cards, children’s book illustrations and calendars. Whereas once economic and/or geographic circumstances had been sufficient to segregate self-taught artists from received culture, in the age of mass communications a further degree of remove seemed to be required. Dubuffet started by collecting the art of mental patients, but like other members of the avant-garde before him, what he was really looking for was an art untainted by the influence of bourgeois civilization: an art that was (as he put it) Brut, or raw.

Art Brut was literally Dubuffet’s invention, and in coining the term, he also created the field. Almost from the outset, however, the term proved impossible to define. Psychiatric art was at least objectively identifiable, even if it raised the ugly specter of classifying artists according to their degree of emotional impairment. But once Dubuffet acknowledged that Art Brut could as readily exist outside the hospital walls as within, he became reliant on far more subjective criteria. How, finally, could one judge an artist’s distance from received culture? Trained artists, after all, do strive to break new ground, and cultural influences penetrate even mental institutions. Admitting that no artist exists either fully beyond or within received culture, Dubuffet proposed the idea of a continuum, along which artists might be situated in accordance with their degree of proximity to or distance from the conventional art scene. Nevertheless, particularly as one moves away from the extreme ends of the spectrum, certifying an artist as Brut entails a very personal assessment of the artist’s motives and mental state. At a certain level, the determination of who is or is not Brut rests as much in the eye (or mind) of the beholder as it does in the art itself.

If there is such a thing as a canon of accepted Art Brut artists, it would have to be those in Dubuffet’s collection, today housed at the Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. Work which Dubuffet did not consider quite Brut enough, he dubbed “Neuve Invention” (New Invention) and housed in a separate annex. In 1972, the British art-historian Roger Cardinal introduced the English-speaking public at large to Art Brut through his book Outsider Art, and in 1979, he and the late Victor Musgrave organized a major exhibition of “Outsiders” for the Arts Council of Great Britain. Today, Monika Kinley continues Musgrave’s work, and the collection she and he formed is on extended loan to the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. Meanwhile, in France, Madeleine Lommel and the self-taught artist Michel Nedjar established the Collection de l’Aracine, which is in the process of being donated to the Villeneuve d’Ascq Museum. Among the other public European collections of self-taught art that have proliferated in the last years are the Haus Cajeth in Heidelberg, the Museum im Lagerhaus in St. Gallen, Switzerland, and the Stadshof Museum for Naive and Outsider Art in the Dutch town of Zwolle. In the small German village of Bönnigheim, Charlotte Zander calls her collection a Museum of Naive Art, but in fact her holdings include a number of Art Brut pieces.

Each of these collections of European self-taught art locates the parameters of the field somewhat differently, and even partisans who stick exclusively to Art Brut are capable of maddening theoretical hair-splitting when it comes to selection criteria. The Naive and Art Brut camps for the most part have little to do with one another, but once one accepts Dubuffet’s idea of a cultural continuum, it can become difficult to draw the line between the Naive and the Brut. Dubuffet, after all, was essentially looking for the same kind of untainted creativity as the original champions of Naive art. And while it is true that the first generation Naives, who created easel paintings in the manner of Rousseau, have an entirely different “look” than the Brut artists, the differences may be more ones of style than substance. Today, the Naive category contains a number of artists who do not do conventional easel paintings….

There are no easy answers to these questions, just as there is, today, no satisfactory definition of Art Brut or Naive art. Perhaps the most that can ever be said is that self-taught artists, as a broad group, are those who fail to partake of the ongoing dialogue amongst artists, critics, curators and collectors that constitutes the mainstream art world; even if discovered and brought into the art world, self-taught artists will never participate fully in that dialogue, because they are by background and nature incapable of doing so. As a result, the intentions, methods and desires of self-taught artists are often given short shrift even by their most impassioned advocates, and self-taught art is instead interpreted in accordance with the mainstream’s agenda. For example, those who oppose bourgeois capitalism are outraged at the idea that anyone (sometimes including the artists) should make money from self-taught art. Many avant-garde artists have used self-taught art to validate their own achievements: to prove that they, unlike their less enlightened colleagues, were not corrupted by the evils of modern civilization. In America, Outsider art has come to represent such quintessential national virtues as rugged individualism, grassroots vitality, ethnic diversity and boot-strap self-reliance. Our beliefs about self-taught art thus often tell us more about ourselves than they do about the artists. Whether Naive or Brut, self-taught art has, throughout the twentieth century, been a repository for our fondest dreams: when we have despaired of civilization, of justice, of the indomitability of the human spirit, self-taught artists have been there to redeem us. In an era when intellectuals tended to cultivate negativity, optimism went underground and emerged in the life-affirming creativity of the unschooled.

Excerpt source:

Jane Kallir, “European Self-Taught Art: Brut or Naïve?” Exhibition essay, January 18-March 11, 2000 (New York: Galeri St. Etienne, 2000).

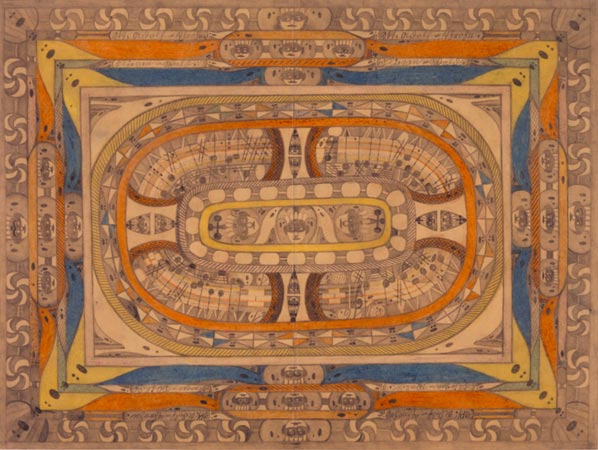

Fliegen-Wald, c. 1921

Pencil and colored pencil on paper

Swiss

2001

Jenifer P. Borum, “ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut,” Folk Art magazine (2001)

Art brut is a uniquely fascinating and often misunderstood category of twentieth-century art. Coined by the French artist Jean Dubuffet during the mid-forties, the term means “raw art” — art that has not been influenced or “cooked” by high cultural aesthetic standards or current art trends. In a polemical essay written in 1949 and intended as an attack against “l’art culturel” (art officially sanctioned by academies, museums, and galleries), Dubuffet clearly and passionately defined this new category: “What we mean is anything produced by people unsmirched by artistic culture, works in which mimicry, contrary to what occurs with intellectuals, has little or no part. So that the makers (in regard to subjects, choice of materials, means of transposition, rhythms, kinds of handwriting, etc.) draw entirely on their own resources rather than on the stereotypes of classical or fashionable art.”[1]

…His search for “people unsmirched by artistic culture” led him away from the sophisticated artworld of which he was admittedly a part to the unlikeliest of places: the psychiatric hospital, the medium’s parlor, the hidden world of the isolate, and the quotidian, workaday world in which artistic talent is often undervalued or ignored. In all these places he discovered art brut, which art historian John MacGregor has effectively characterized as “the spontaneous creative activity of artistically untrained men and women working alone outside of any artistic movement or cultural influence, motivated by an intense inner need to make images and free of any concern with art.”[2]

Dubuffet was certainly not the only one with an appetite for “uncooked” modes of expression. His interest in art created by the insane had been sparked as early as 1923 by the seminal book Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1923), by the psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn, who dared to defend the inherent aesthetic value of art produces by psychiatric patients. Dubuffet’s fascination with the art of psychotics and mediums was also presaged by the advocacy (and appropriation) of such art forms as the Parisian circle of Surrealists led by André Breton. Initially intending to publish a series of studies on art brut, Dubuffet made a pilgrimage to a number of Swiss asylums in 1945. During this time, he began to collect the work of psychotic artists such as Adolf Wölfli and Aloïse Corbaz, and the Collection de l’Art Brut was born. With Breton and a number of other sympathetic artists and poets, Dubuffet formed the Compagnie de l’Art Brut for the purpose of building, maintaining, and exhibiting the Collection. The legacy of the Compagnie includes a series of books begun in 1964, a major exhibition of art brut at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1967, and the establishment in 1976 of a permanent museum for the Collection at the Château de Beaulieu in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Jennifer P. Borum is a Ph.D. candidate in art history at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. She is a lecturer at the Museum of American Folk Art’s Folk Art Institute and has written for Art-forum, The New Art Examiner, Raw Vision, and this publication.

[1] Jean Dubuffet, “Art Brut Preferred to the Cultural Arts,” exhibition catalogue (Paris: René Drouin Gallery, 1949), translated in Mildred Glimcher, Jean Dubuffet: Toward an Alternative Reality (New York: Pace Publications, Inc. in association with Abbeville Press Publishers, 1987), 101-104.

[2] John MacGregor, The Discovery of the Art of the Insane (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), 301.

Excerpt source:

Jenifer P. Borum, “ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut,” Folk Art magazine, Spring, 2001, 26-33.

2001

The Collector in Context an Essay by Jane Kallir

Introduction to Self-Taught & Outsider – The Anthony Petullo Collection. University of Illinois Press.

2004

Scottie Wilson – Peddler Turned Painter – Petullo Publishing, LLC (2004) Anthony J. Petullo and Katherine M. Murrell

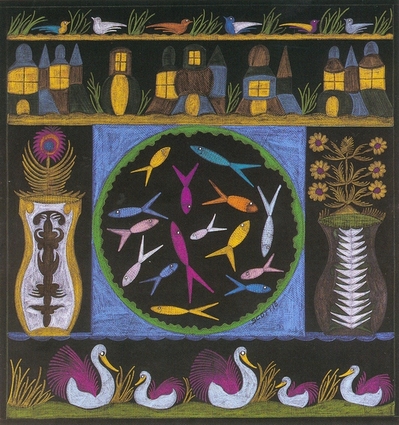

Center Fish Circle on Black, c. 1965

Colored ink on paper

British

Scottie Wilson (1891–1972) was a self-taught artist who achieved recognition from both the art world and the popular media. Nevertheless, he remained an outsider who lived modestly and would sell his pictures to people he met on the street for a fraction of what they sold for in galleries. The child of Eastern European émigrés, Scottie (born Lewis Freeman) grew up in the poor, predominantly Jewish Gorbals section of Glasgow. He left school at the age of nine, worked at a number of odd jobs, and after a period in the military (which included serving on the Western Front during World War I), established himself in London as a dealer in secondhand goods.

In the 1930s Scottie moved to Canada, and it was there, in the back room of his shop, that he discovered his vocation as an artist. Once he began drawing, he never stopped, and he eventually began to show his work throughout Canada. Scottie’s works are typically rendered in a distinctive hatching technique, and early pieces are characterized by mysterious faces termed “evils and greedies,” while his later drawings and paintings are surprisingly idyllic, dominated by vividly colored flora and fauna.

In 1945 Scottie returned to London, where he initially exhibited with the Surrealists, who saw affinities between his inventive imagery and their own art. He later traveled to France to meet artists Jean Dubuffet and Pablo Picasso, who both acquired examples of his work, and in the 1960s he received commissions to design patterns for ceramics and textiles. Despite his successes, Scottie remained aloof from the cultural establishment, viewing his utopian images as providing an alternative to “this wicked world.”

Scottie Wilson: Peddler Turned Painter tells the fascinating story of this complex and enigmatic figure, presenting many new biographical details, based on extensive research, and tracing the evolution of his art. The color plates illustrate works in various media spanning the length of Scottie’s career, and this volume includes a selection of remarkable black-and-white portraits of the artist.

Excerpt source:

Anthony J. Petullo and Katherine M. Murrell, Scottie Wilson: Peddler Turned Painter (Milwaukee: Petullo Publishing, 2004)

2005

Katherine M. Murrell, “Art Brut: Origins and Interpretations,” Singular Visions: Images of Art Brut from the Anthony Petullo Collection exhibition essay (2005)

Sixty years ago, Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) wrote in a letter to his friend, the painter René Auberjonois:

“I preferred ‘Art Brut’ instead of ‘Art Obscur’ [Obscure Art], because professional art does not seem to me any more visionary or lucid; rather the contrary….Why then do you write that gold in its raw state is more fake than imitation gold? I like it better as a nugget than as a watchcase. Long live fresh-drawn, warm, raw buffalo milk.”(1)

This is the first recorded use of the term Art Brut, often translated as “raw art.” With this, a field of study was born. However, the parameters that defined exactly what this meant had yet to be determined, and there is still much debate about what does and does not constitute Art Brut, or the later term, Outsider Art.

As Dubuffet described it, this was art that was not based on established traditions or techniques. It did not follow styles or trends, and it was not made primarily to be sold for monetary gain. It is spontaneous, uninhibited, and maybe not even made as “art.” The appeal of this work, for Dubuffet and others before him, was the unselfconscious imagery born of pure, uninhibited expression. This art subverted the conscious efforts of the artist and dismissed premeditated ideas of what art should be and what it should represent.

This type of activity, from outside established art academies and beyond the scope of tradition and history, has always been around, but because it was not valued in its contemporary society, was seldom preserved for future generations. In the twentieth century, with the development of a modernist approach in art and the exploration of alternate forms of visual representation, besides what is generally included in the western art historical canon, interest grew in these types of work, prompting their preservation and study.

In his attention to the artistic output of institutionalized people, Dubuffet was following in the footsteps of predecessors such as Dr. Hans Prinzhorn, a Viennese psychiatrist who had been trained as an art historian in the early twentieth century. In his medical practice, he came in contact with the drawings of patients who exhibited striking aptitudes for visual expression. His writing on the subject, particularly in the form of his 1921 book Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill), circulated in Europe and was a topic of interest among avant-garde artists as they sought new modes of expression in their work. Prinzhorn discussed the artistic output of the individuals partly in terms of representing an urge to communicate, to externalize imagination, emotions and responses.

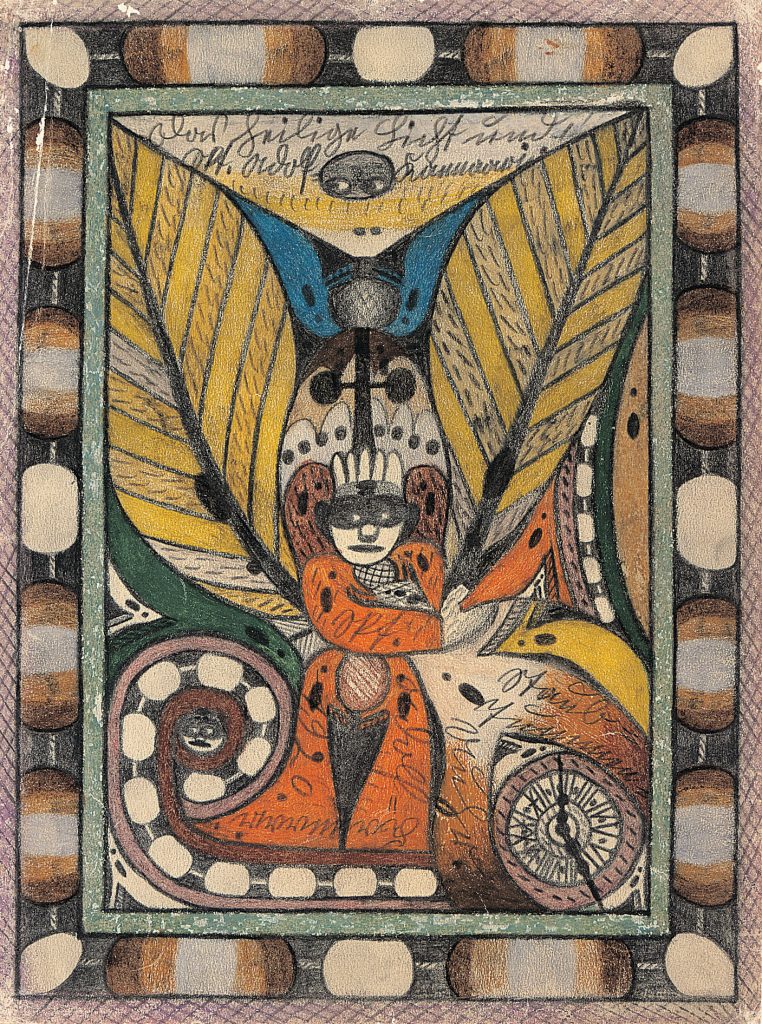

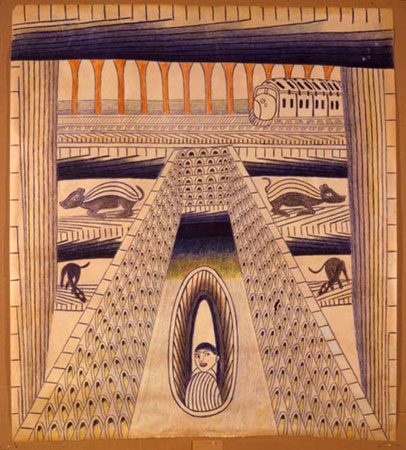

Angel, 1920

Pencil and colored pencil on paper

Swiss

Another key scholar in the early twentieth century was Dr. Walter Morganthaler. He extensively studied Adolf Wölfli (1864-1930, Swiss), who spent the final thirty-five years of his life in an asylum. Wölfli’s massive oeuvre consists of numerous volumes of writing, including a semi-fictional autobiography of nearly three thousand pages. His works are highly complex and use careful gradations of color and intricate pattern, often with figures and self-portraits as part of his conceived universe. In addition to writing and image making, musical notes appear in his drawings, showing compositions that he would play on a horn made of cardboard.

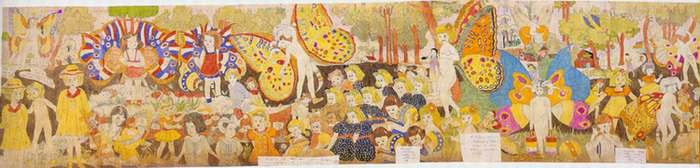

Blengiglomeneans Displaying their Wings, n.d.

Watercolor, pencil, carbon and collage on paper

American

As a characteristic feature of Art Brut, there is often a personal intentionality that distinguishes it from mainstream or commercial art, or pieces meant to appeal to an intended audience. As with Wölfli, works may be produced to give visual presence to an intellectual universe, leading to a possible position where the drawings invade or supplant reality. Henry Darger (1892-1973, American), who lived in Chicago nearly his entire life, created a staggering quantity of work which consisted of written and visual productions. His literary magnum opus is an epic novel of over fifteen thousand pages, commonly known by its abbreviated title, In the Realms of the Unreal. Darger’s work is strongly related to this massive tome, and inventive in his use of various techniques, incorporating appropriated and original material into scenes of exceptional color and compositional quality, employing these formal concerns in both scenes of strange and idyllic beauty and shockingly violent subject matter.

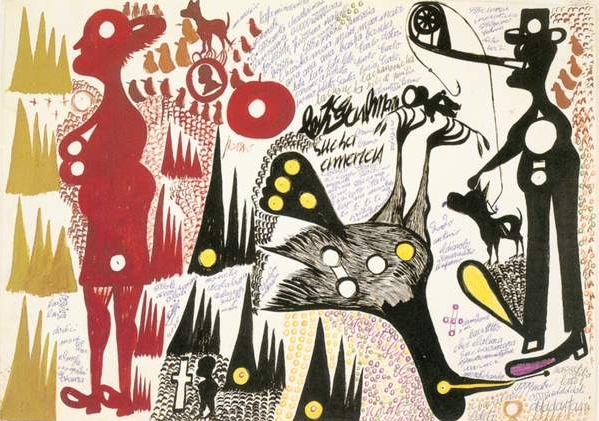

Untitled, n.d.

Ink on card

British

Whereas the work of Wölfli and Darger finds a common denominator in the connection of visual and literary expression, other artists had a more ethereal impetus in their work. Madge Gill (1882-1961, English), was highly influenced by Spiritualism, a movement interested in contact with the dead and otherworldly phenomenon. She began drawing in 1919, believing her work was guided by a spirit she called Myrninerest, and refrained from selling her work during her lifetime for fear of angering the spirit. Her ornate compositions are typically populated by elaborately robed women in architectonic settings, peering from her drawings with mysterious eyes.

Temple of Light, c. 1942

Colored pencil and ink on paper

British

The early work of Scottie Wilson (1891-1972, Scottish) shares some of these enigmatic qualities. Wilson received much recognition during his lifetime, but remained aloof from the art world, preferring in fact, to subvert it at times. He began drawing in Toronto in 1935 and resettled in Britain after World War II. His work was shown in galleries, but while his drawings could be sold for a hundred pounds in these shops, he would sell them for a couple of pounds in the street. Wilson’s work was collected by Pablo Picasso and Jean Dubuffet, who included him in his collection of Art Brut. The visionary quality of Wilson’s work, exemplified by the “evils” and “greedies,” or leering, frightening faces in his drawings, signified negative forces of the world, which Wilson believed could be neutralized through his drawings.

Despite Wilson’s seeming inclusion in the London art world, Dubuffet found him to be impervious to the market and essentially devoid of interest in art except his own. In his drawings, Dubuffet found the characteristics of Art Brut, such as a lack of premeditation as seen in the academic or trained artist, whose work is almost unavoidably conscious of tradition, audience, and marketplace. Whereas Prinzhorn viewed works which would become part of the Art Brut canon from the standpoint that the creators made these pieces as a means of externalizing sensation, Dubuffet’s interest lay in their stature as uninhibited and nonconforming to generally accepted expectations of culture. In fact, the status of this work as largely unaffected by culture is what Dubuffet valued most about it. However, defining its absolute relationship to established modes of convention is often difficult, and the delineation of cultural boundaries unclear.

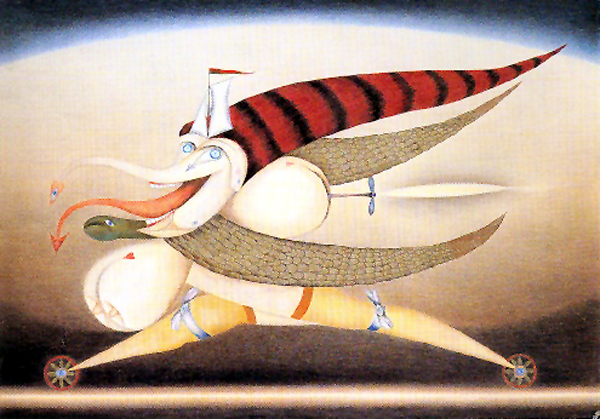

Courtyard (#208), 1954

Mixed media on paper

Mexican

In the work of some artists often considered within the Art Brut canon, there are strong cultural overtones. Martin Ramirez (1885-1960, Mexican) came to the United States probably in the first decade of the twentieth century and worked on railroads in southern California. He became indigent, and was eventually placed in a state mental hospital. Long believed to have been mute, it seemed that drawing was a means of communication and externalizing his memories and experiences of Mexico and America. His compositions incorporate imagery that references his native culture, and recurring motifs such as trains and animals, as well as repeated geometric and decorative patterns.

Because of the difficulties inherent in the attempt to precisely define the boundaries of Art Brut, Dubuffet found it necessary to determine another related category of art, which he called Neuve Invention (Fresh Invention). This definition included artists who fit to some extent the conditions of Art Brut, but demonstrate a somewhat closer relationship to received culture and society. This is naturally a more inclusive area, and filled with artists whose work is quite powerful as well. In the French parlance, there is also a discrete segment of the field known as Art Singulier, coined in 1978 by Alain Bourbonnais, which accents the individual position and purpose of the creator.

Die Damonin der Eile (The Demoness of Urgency), 1958

Pastel on cardboard

German (b. Lithuania)

In the broader scope that encompasses Art Brut and works termed Neuve Invention, there are commonalities. As a general characteristic of approach, there is a predilection for highly imaginative and extraordinary compositions that deviate from traditional art historical genres such as portraiture, still-life, landscape, and the like. Images are often disembodied and presented with a sense of being disjoined from reality or tangible conditions.

Untitled (red form), n.d.

Pastel on paper

Moravian (Czech Republic)

This sense of departure can be seen in the work of Friedrich Schroder-Sonnenstern (1892-1982, Lithuanian). Most active in his drawing in Germany, he created fantastic, bizarre, and often sexually charged compositions with smooth, precise forms and vibrant color. The drawings of Anna Zemankoa¡ (1908-1986, Moravian) are also unbound from strictly observed reality. She develops large, organic forms; they are flower-like without being real flowers, they are purely imaginary. Carlo Zinelli (1916-1974, Italian), incorporates images from his life experience and reiterates them in a manner that denies easy narrative sequences, but strongly evokes emotional content through the manipulation of forms, figures, and relationships within the composition.

Untitled, n.d.

Tempera on paper

Italian

Three Figures and a Dog, 1972

Oil crayon on paper

American

The repetition of motifs and style reveals another characteristic in this genre. It is common for these artists to begin working in a particular style, and for there to be little deviation from that mode. Though their techniques and handling of materials often becomes more sophisticated, the degree of experimentation in style or method is relatively slight. Eddie Arning (1898-1993, American) produced the bulk of his drawings based on advertisements from commercial media, and though he used a variety of source materials, he was rigorously consistent in his methods of constructing compositions and rendering figures. Dwight Mackintosh (1906-1999, American), whose work was primarily created at the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, California, also displays stylistic consistencies. His drawings of figures are energetically linear and selective in the use of color. Wavy lines in many of his works are likened to text, suggesting an externalization or means of communication through art.

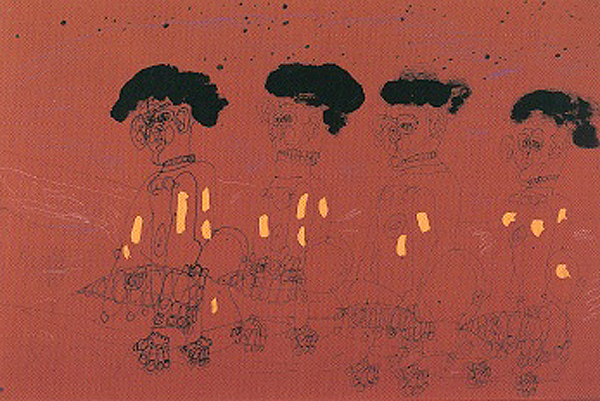

Four Men, 1984

Ink and tempera on rust colored paper

American

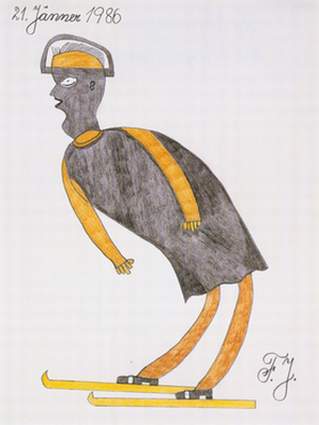

Woman Ski Jumper, 1986

Pencil and colored pencil on paper

Austrian

A workshop outside of Vienna, established in 1982 at the Klosterneuburg Hospital in Maria-Gugging, Austria, called the Haus der Künstler (House of Artists), is a place where patients demonstrating artistic aptitude live and work. Despite being in close quarters, each maintains a highly individual style. Johann Fischer’s (b. 1919, Austrian) early work is characterized by the depiction of geometrized, solitary persons in black, brown and yellow, but in his later work, narratives are added that surround and engulf the figures. Oswald Tschirtner’s (b. 1920, Austrian) work is elegantly minimalist, in sharp contrast to that of August Walla (1936-2001, Austrian), whose compositions are bright and filled with powerful figures, using numerous symbols and signs in a cacophony of iconography. Johann Garber’s (b. 1947, Austrian) ink drawings often exhibit a sense of horror vacui, a tendency to obsessively fill space with minute detail and decoration. He uses similar forms in his color works, but with less density.

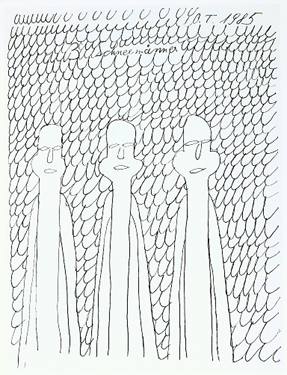

Drei Schneemaner (Three Snowmen), 1985

Ink on paper

Austrian

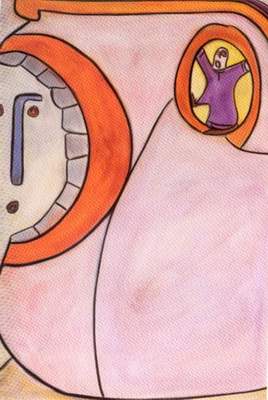

Golderne Schrebergartenhuetten, 1985

Pencil, colored pencil, pen, and crayon on paper

Austrian

Untitled (11/16/89), 1989

Ink on paper

Swiss-American (b. Germany)

Many of these artists today are called “outsider artists,” a name which was derived from the title of English art historian Roger Cardinal’s 1972 book, Outsider Art. In Britain and America, this name became popular instead of the French moniker, Art Brut. The introduction of this additional, or in some respects alternate, term reflected the complexities of attempting to encapsulate the enormous diversity of creative production. Numerous artists practicing today are considered in this field, such as Rosemarie Koczy (b. 1939, American/Swiss), a Nazi concentration camp survivor whose work is an ongoing memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, and Michel Nedjar (b. 1947, French), whose painted works are solely done on found materials and resonate with a totemic quality. Albert Louden (b. 1943, English) is best known for his bulbous figures in strange, jumbled settings whose joys and apprehensions are reflective of the modern urban experience.

Untitled (gold figure), 1991

Mixed media on paper

French

Untitled, 1988

Pastel on board

British

The field of Art Brut today is a scene of intense study and perpetual debate about its relation to art, culture, and our perceptions of it. Over time, Outsider Art has erroneously been used to describe everything from works by self-taught and folk artists, to art produced in therapy programs, and art made by those who are maybe just a bit eccentric. At the heart of Art Brut is a reflection of the artist that is intense, original, and essentially positions the viewer as voyeur, suddenly a party to this private imagery. In this sense, we occupy a special position, and may be seen as the outsiders looking in on these singular worlds.

(1) Letter from Dubuffet to René Auberjonois, August 28, 1945. Printed in Jean Dubuffet, Prospectus et tous écrits suivants, tome II (Gallimard, 1967), 240. Translation from Lucienne Peiry, Art Brut: The Origins of Outsider Art (Paris: Flammarion, 2001), 39.

Essay source:

Katherine M. Murrell, “Art Brut: Origins and Interpretations,” Singular Visions: Images of Art Brut from the Anthony Petullo Collection exhibition essay, September 16-December 31, 2005 (Chicago: Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 2005).

2006

Jon Thompson, “The Mad, the ‘Brut’, the ‘Primitive’, and the Modern: A Discursive History,” Inner Worlds Outside exhibition catalogue (2006)

With the intervention of the French painter Jean Dubuffet, the overarching regime of interpretation governing Art Brut or Outsider Art shifted quite dramatically from psychiatry into the more open domain of the visual arts. He worked in secret to expand the definition of Art Brut and to widen the search for exemplary figures. However, there was always a certain ambivalence about Dubuffet’s formulation and an element of denial foreshadowed by the very label with which he chose to describe it, Art Brut (raw art). His initial impulse was to make a collection that was accessible to only a select group of people but not to the public and to ‘ear-mark’ but not to define the Art Brut artist. Dubuffet’s founding ambivalence continues to the present day. Paradoxically, despite his passionate interest in the work of artists who lived and worked independently of the mainstream and his pioneering work in bringing such work together as a collection, he remained a convinced ‘separatist’. He wanted the achievements of these artists to be recognised but kept apart from the art of the Modernist, or as he called it ‘academic’, mainstream. Even after his collection had been given its own museum in Lausanne, he insisted on a singular highly restrictive condition for its future use: no work from the main collection was ever to be removed and used in curatorial projects in other museums.

But the most problematic aspect of Dubuffet’s ‘separatism’ adheres to the term Art Brut itself, with its implications of a ‘founding’ or ‘originating’ creative impulse as an antidote to an overly cultured art. Accordingly, image-wise Art Brut figures as a pure, stylistically autonomous, a-historical, unschooled art, arising out of the burning inner necessity of individuals who are detached from cultural processes and institutions and exist beyond the margins of ‘normal’ society. The impossibility, perhaps even the absurdity, of such an existence is clear. Examine each point of definition in turn and there quickly emerges something of [Roland] Barthes’ hysterical mimodrama in such a self-reflecting and overly simplified ‘representation’ of creative life. Look closely at the work of artists like Henry Darger, Joseph Yoakum, Scottie Wilson, or even that of Adolf Wölfli who was hospitalized with psychosis and this highly restrictive, ultimately negative picture is rendered fugitive. Clearly these artists — and many others like them — enjoyed rich imaginative lives. How these lives were fed varied with individual circumstances….All four, then, were very much concerned with the wider world, even with imagined sites far removed from their immediate day to day circumstances.

Excerpt source:

Jon Thompson, “The Mad, the ‘Brut’, the ‘Primitive’, and the Modern: A Discursive History,” Inner Worlds Outside exhibition catalogue (Fundación “la Caixa”; Irish Museum of Modern Art; Whitechapel Gallery, London; 2006), 65-66.

2006

Roger Cardinal, “Worlds Within,” Inner Worlds Outside exhibition catalogue (2006)

Nonetheless, having conceded that Outsiders do not invent everything ex nihilo, I must return to my theme with vigour, stressing that it is the use made of the material that matters, not the source per se. Imagining means taking hold of certain perceptions, images or ideas that have entered consciousness from outside and recycling them in original patterns and juxtapositions. By definition, no Outsider of stature will wish to bow to an external authority. Having once adopted a motif, he or she will want to implement it within their personal scheme, stripping it of its old associations and investing it with fresh meaning. In the end, Willem van Genk’s exhilarating multi-perspectival renderings of Amsterdam, New York or Moscow have as much documentary value as Yoakum’s fanciful renderings of the Andes or the Holy Land. In a superficial sense, their iconography could be said to be indebted to reality; but it is more pertinent to say that the real has been appropriated and converted into a property of the imagination, equating to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s idea of the painting which offers us a glimpse of ‘what is woven within interiority, the imaginary texture of the real’. [1]

[1] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, L’Oeil et l’espirit (Paris: Gallimard, 1985), 24.

Excerpt source:

Roger Cardinal, “Worlds Within,” Inner Worlds Outside exhibition catalogue (Fundación “la Caixa”; Irish Museum of Modern Art; Whitechapel Gallery, London; 2006), 24-25

2009

Anthony Petullo, “Art Without Category,” Milwaukee: Petullo Publishing LLC, 2009

Over the past 20 years Anthony Petullo has assembled an outstanding collection of works by artists who are often described as “self-taught,” “naïve,” or “outsider.” In Art Without Category, he calls those labels into question, exploring the lives and work of 10 extraordinarily gifted artists from Great Britain and Ireland who operated outside the artistic mainstream, determinedly and sometimes obsessively pursuing their singular visions. All received some degree of recognition during their lifetimes, yet they are, as Petullo writes, “orphans without an art family,” creating works that do not fit into the conventional narrative of twentieth-century art. This abundantly illustrated volume, which includes an introductory essay as well as a biography of each artist, demonstrates that they are nevertheless an essential part of the story.

2012

Accidental Genius – Art From The Anthony Petullo Collection Milwaukee Art (2012)

with an introduction by Jane KallirDownload

This text is reprinted with permission from the publication, Accidental Genius: Art from the Anthony Petullo Collection (Milwaukee Art Museum and DelMonico Books•Prestel, 2012) book: https://delmonicobooks.com/book/accidental-genius-art-from-the-anthony-petullo-collection/