One of the most interesting facts about the self-taught and outsider artists like those in the Anthony Petullo Collection, is that so many of them were discovered by well known, and sometimes quite famous, artists. Others were discovered by psychiatrists with a strong appreciation for art who worked in Swiss, Austrian and American mental hospitals. Unlike so many other genres, these self-taught artists were not sought out and promoted by art dealers.

Paul Klee was an early advocate of mental patient art, as was Dr. Walter Morgenthaler and Dr. Hans Prinzhorn in the 1920’s. In the decades following, notable artists Ben Nicolson, Christopher Wood, Jean Dubuffet, Pablo Picasso, the Surrealists, and the Chicago Imagists all became advocates and collectors of the self-taught and outsider artists.

Those superbly accomplished artists and a host of contemporary artists all recognized the genius of these self-taught artists and their influence on the trained artists. The naive, intuitive, primitive and outsider artists were inspiring and liberating. Frequently, these very simple people appeared at a time when the artistic giants of the twentieth century were looking for a new direction.

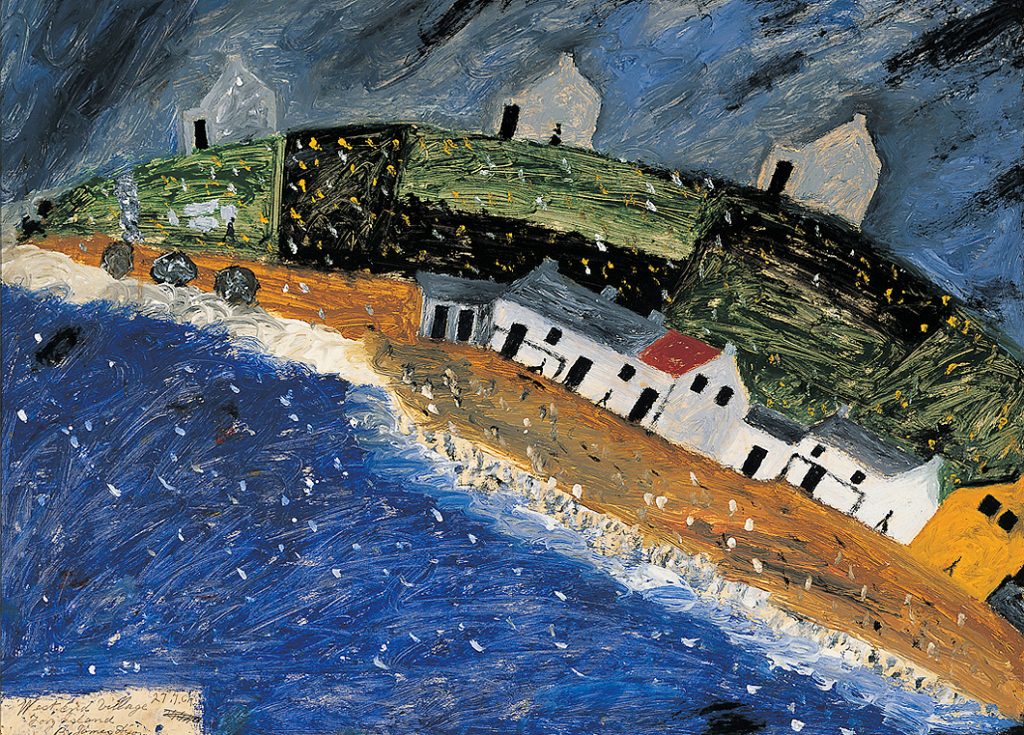

The stories begin with English artist, Alfred Wallis, in St. Ives, at Land’s End in Cornwall.

It was a hot day in August 1928. Christopher “Kit” Wood had been to St. Ives before and on this trip he had encouraged Ben Nicholson to come along. They had a driver take them to a very high point overlooking St. Ives and the harbor. The view was spectacular. After a morning of painting, Nicholson and Wood were wandering along Back Road West when they noticed, through the open door of No. 3, a naive painting of houses and ships nailed to the wall.

“Look at those!” said Nicholson. “We must go in.” And with Wood at his heels he entered the cottage to find Alfred Wallis working at a table , looking as a fellow St Ives artist Adrian Stokes said, “just like Cezanne.” When Wallis was asked if he would sell some of his paintings, and how much he wanted for them, he confessed he had never thought about it. He painted simply “for company’ as he was lonely after his wife’s death.

Some time later, Christopher Wood said, “I’m not surprised that no one likes Wallis’ painting. No one liked Van Gogh’s for a time, did they.” (Alfred Wallis: Primitive, Sven Berlin)

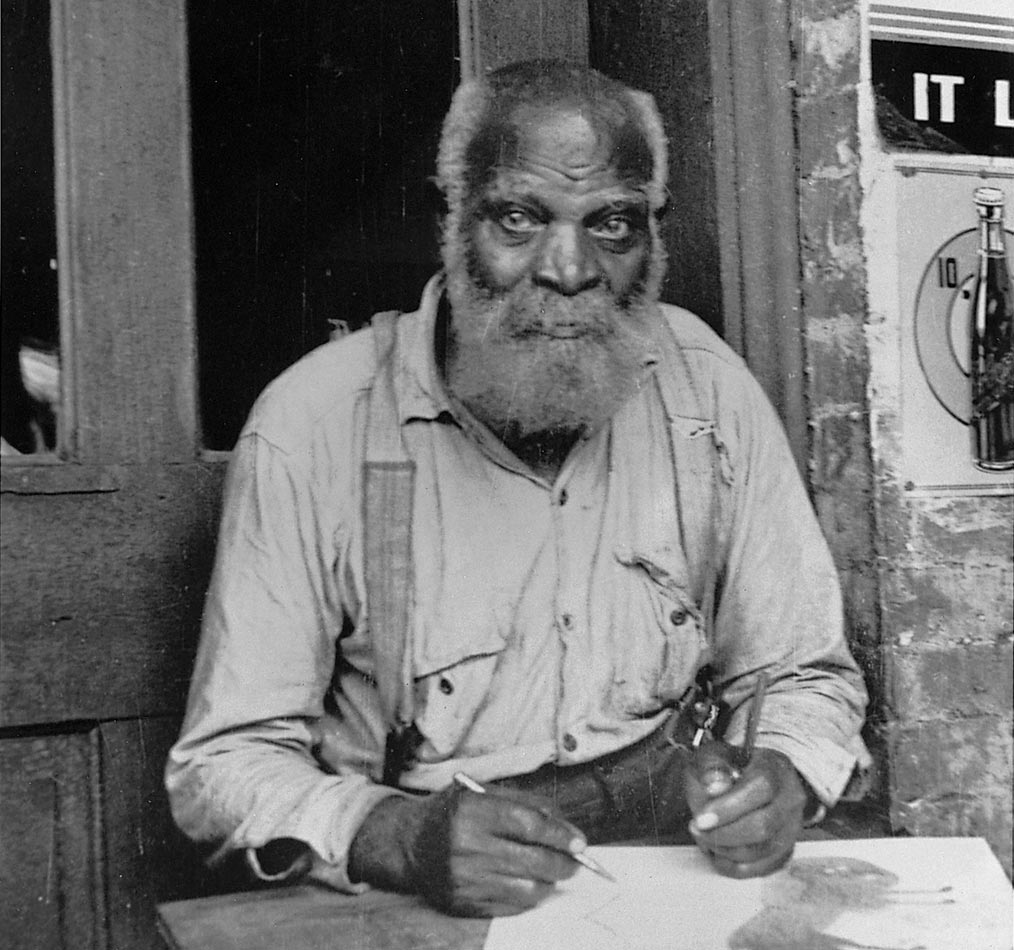

A few years later, in 1939, professional artist, Charles Shannon had a chance meeting with Bill Traylor in Montgomery, Alabama. Traylor used to sit on a box on a busy sidewalk while drawing on pieces of cardboard. Bill Traylor had a lot in common with the English artist Alfred Wallis. Both had worked hard all their lives for very little money and had almost nothing. They were semi-literate. Wallis was a retired mariner and Traylor, born into slavery in 1854, become a share-cropper on the Traylor plantation after abolition. Wallis slept in a flee-infested room and Traylor slept in a room behind a funeral parlor. Both were widowed and drew pictures to pass the time, or, as Wallis said, “for company.” Traylor was given a few dollars for his works, which quite amazed him.

Because of their devoted advocates, Wallis and Traylor would become very important twentieth-century artists. Wallis is well represented at the Tate Museum in London, and Traylor at the Modern Art museum in NYC, and both are represented in many prestigious collections, including mine. Traylor’s works are now sold at contemporary auctions, as well as self-taught, in the US and Europe, and prices for the best of each artist’s works can be very expensive.

There are countless stories of chance meetings between self-taught artists and professional artists. The meeting between English painter Derek Hill and Irish painter James Dixon is a classic tale. I asked Derek Hill to write about James Dixon for my book Art Without Category: British & Irish Art From The Anthony Petullo Collection. He wrote, “I met James Dixon on my first visit to Tory Island in 1956. I was painting near the harbor and several islanders came to watch. ‘I can do better than that,’ he remarked, to which I replied that he should paint a picture and show it to me. I provided him with paints and paper, which he preferred to canvas. He said he made his own brushes out of his donkey’s tail hairs. ‘This is a good one,’ he used to say when he showed me what he’d done.”

Ten years after that hill-top meeting, James Dixon had a one-man exhibition at the Portal Gallery in London, and Hill wrote the introduction for the catalogue. He was Dixon’s friend and his advocate.

Canadian art dealer Douglas Duncan discovered Scottie Wilson and his magical drawings in the early 1930’s. The bored Toronto secondhand dealer made his first drawings on a tabletop in the back of his shop. Wilson eventually was given exhibitions at major Canadian museums before returning to his native England after WWII. London art critic Bill Hopkins told his story in my book, Scottie Wilson Peddler Turned Painter. Early in the 1950’s, Jean Dubuffet, the discoverer of Art Brut and already a collector of Scottie Wilson’s drawings, resolved himself to finally meet the artist after seeing his work at a surrealist exhibition in Paris.

When Wilson received Dubuffet’s letter inviting him to Paris and bring his portfolio, he didn’t know anything about Dubuffet or “Art Brut” but the prospect of selling his drawings appealed to him. Since Bill Hopkins was a close friend to Scottie, he insisted that Bill accompany him. Like a cat, he was always wary of strangers. When they arrived, not only was Dubuffet waiting, but Pablo Picasso was, too. Both owned a few of Scottie’s pieces, and Picasso had come to see more of Scottie’s work, and perhaps buy more, provided that Dubuffet would leave a few for him.

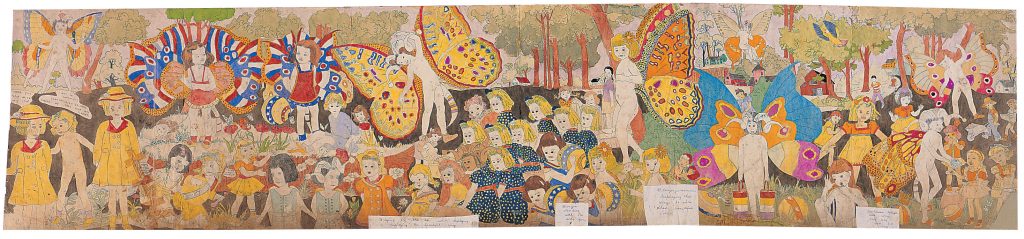

Meanwhile, in a rather small rented room on the north side of Chicago, Henry Darger continued his 15,145 page typewritten manuscript, In the Realms of the Unreal, his epic saga of an imaginary world in which a brutal war was fought between nations over the enslavement of children. The saga then was illustrated on sheets of paper from six to twelve feet in length. However, his landlord and discoverer-advocate, photographer Nathan Lerner, didn’t see the full extent of Darger’s work until Henry was near death in 1973. By coincidence, as a young boy I lived three blocks from Darger, where my parents owned a sundries store with a large supply of candies. Darger’s biographer, John McGregor, told me that Darger had a sweet tooth and loved candy. Perhaps Henry was one of our customers.

We have psychologist and advocate, Dr. Tarmo Pasto, to thank for saving the works of Martin Ramirez, the Mexican who spent many years in California mental hospitals. Dr. Pasto later introduced the work to Chicago artist, Jim Nutt, then a teaching assistant in California. Ramirez has become one of the most important figures in the American self-taught art world. Yet, until recently, little was known about this amazing artist. But Victor and Kristin Espenosa have uncovered considerable information about Ramirez, his family and his stay at the mental hospitals. Victor was born in the same Mexican state as Ramirez.

Dr. Pasto wasn’t the first to appreciate the work of mental patients. In 1912 Paul Klee said that the art of the mentally ill “really should be taken far more seriously than are the collections of all our art museums if we truly intend to reform today’s art”. In the works of the mentally ill, Klee discerned “depth and power of expression….really sublime art. Direct spiritual vision”. Paul Klee found confirmation of his own art in the works collected by Dr. Hans Prinzhorn.

Art dealer and historian Jane Kallir writes, “In 1921 Walter Morgenthaler published his monograph on Adolf Wolfli, A Mentally Ill Person as an Artist. And in 1922, after a marathon three-year collecting spree, Hans Prinzhorn issued his landmark survey, The Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Both authors were psychiatrists who had initially encountered their subjects in clinical settings, but they broke new ground in recognizing that the work of the mentally ill could also be appreciated as art.”

Kallir continues, “Unlike naive art, which in the interwar period was finding its way into galleries, museums and private collections, partly aided by the artists themselves, the art of the mentally ill remained largely the province of a few specialized connoisseurs. Such art was too difficult to attract a wide public at this time, and hospitalized artists were for the most part unavailable or unable to engage in self-promotion. However, the Morgenthaler and Prinzhorn books did reach the right people. A number of German Expressionists made pilgrimages to the Prinzhorn collection at the University of Heidelberg’s Psychiatric Clinic, and Prinzhorn’s book became the ‘Bible’ of the French Surrealists.”

Perhaps the most noted advocate and collector of hospitalized artists was French artist, Jean Dubuffet. Dubuffet toured mental hospitals looking for art that was untainted. The art he found he called Art Brut or raw art. The collection he amassed is now housed at the Musee de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland. Later Dubuffet’s interests extended beyond the hospitals and he began to include artists who were not mental patients in his collection of Art Brut One of those was spiritualist Madge Gill. Gill was guided by her personal spirit, Myrninerest, and she refused to sell any of her artwork for fear her spirit would become angry. After Gill’s death, her estate made the works available to the art world. Among others in the Petullo Collection, are Scottie Wilson and Albert Louden.

As a contemporary advocate for self-taught artists, I am very grateful to those early advocates, professionally trained artists, doctors, and astute collectors – who had the keen eyes to see the genius of these artists, and the courage to promote them. But this early advocacy did not cause an immediate stampede to buy. A few artists had some degree of success but most were not recognized or appreciated for decades.

Even the great Henri Rousseau, one of the greatest of all self-taught artists, was not accepted by the French Academy. Pablo Picasso was one of only a few, mostly artists, who could see his genius. Of course, it was Picasso who also collected the works of Scottie Wilson and other self-taught artists.

It’s been a century since Paul Klee, Dr. Morganthaler and Dr. Prinzhorn first called attention to the artwork of mental patients. And almost as long since Ben Nicholson told Tate Museum curator, Jim Ede, about Alfred Wallis. And more than 70 years since Charles Shannon boxed up more than 1,200 Bill Traylor drawings because no one wanted to buy any.

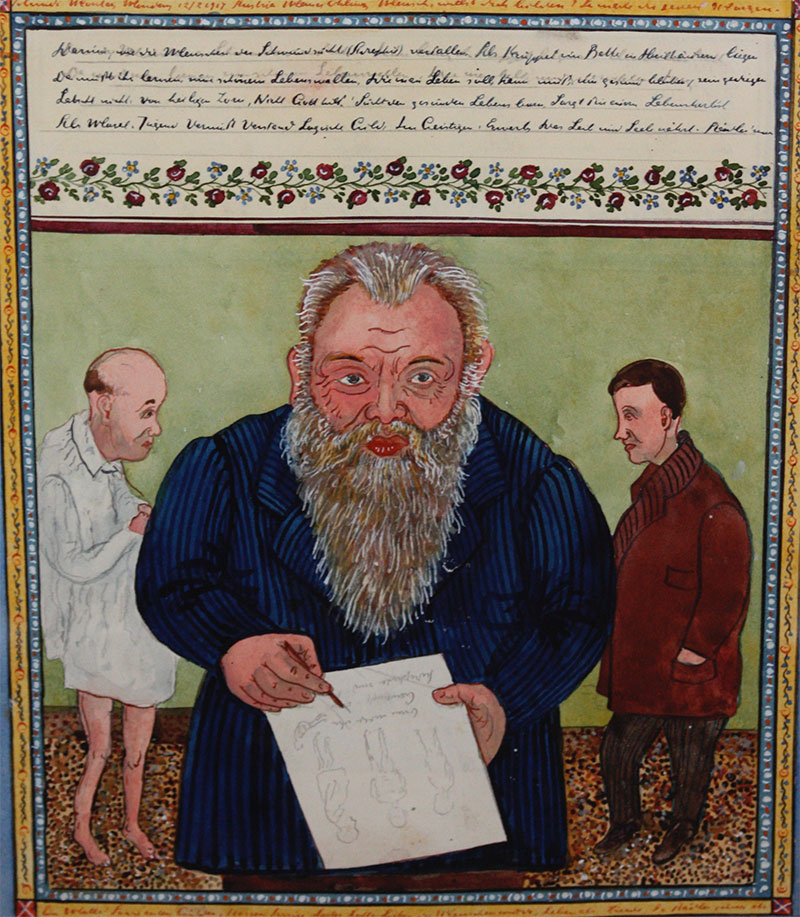

And yet there are some artists in the Petullo Collection whose works have been newly discovered, even though the art was produced more than 100 years ago. For example, Josef Karl Radler produced his last art as a patient in a Viennese mental hospital in 1917. Fortunately, the husband of a hospital staff member salvaged the entire body of Radler’s work from the trash heap, much like Dr. Pasto prevented the hospital cleaning staff from tossing out the Ramirez drawings. Radler’s drawings only became available early in this century and the Petullo Collection was fortunate to acquire six works from the Gallery St Etienne in NYC.

Man, Do You Want to Educate Yourself? Think Up a New Slogan Every Morning (self-portrait), 1917

Watercolor, gouache and pencil on paper

English pointillist, James Lloyd, was discovered and promoted by Sir Herbert Read, poet, scholar, literary and art critic, and the same man who helped Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson establish their work. And yet naive painter, James Lloyd, today is virtually unknown in England. The Anthony Petullo Collection exhibitions was the first exposure to Lloyd in America.

Lloyd used to paint at a kitchen table surrounded by his wife, five noisy young children, a TV and a record player. He rode his bicycle to and from his many jobs, led a quiet, ordinary life, and painted in the evenings to pass the time. Lloyd wasn’t that keen on making a living from his art, but his wife did write to Sir Herbert Read whom she had discovered to be living nearby. Read and fellow critic, John Berger, bought Lloyd’s work, encouraged him to do more, and brought him to the attention of London dealers.

Eventually, a British company made a film about Lloyd and he did enjoy some artistic success during the 60’s and early 70’s.

The artists from the Petullo Collection highlighted in this essay include a retired rag and bone man, a former slave, a fisherman, a junk shop dealer, a janitor, a village policeman, a spiritualist and mental patients. As a lot, they didn’t have much, some very poor, others of only modest means. Two were illiterate and some had only a couple of years of education. Yet, they all were greatly admired and championed by famous artists, doctors and collectors. These admiring advocates were responsible for bringing some very talented and ground-breaking artists to the attention of the cultured art world.

It has been said many times that what the great self-taught artist produces throughout his career is what the trained artist aspires to achieve at the pinnacle of his career.

Anthony Petullo

October 2020

The Anthony Petullo Collection