Patrick Hayman

1915–1988, English

Tags: Painting

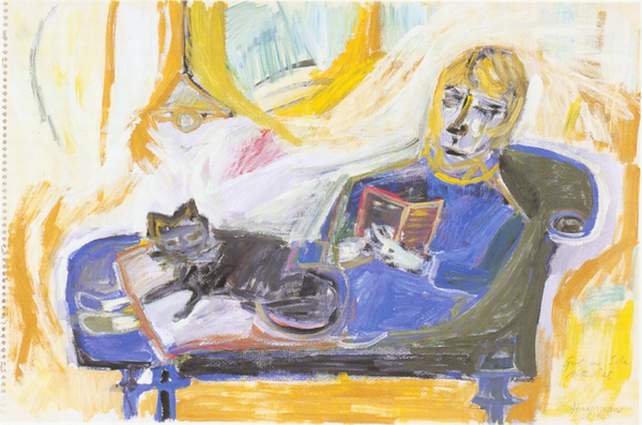

Patrick Hayman imbued his paintings and poetry with symbolism and allusions to myth, history, and literature, often creating allegories that comment on contemporary events. An avid reader, Hayman developed a keen interest in art and literature at a young age, which resulted in a lifetime of making as well as his founding and editing of a literary magazine and an international journal of the visual arts.

Hayman grew up in London. His work evinces a deep connection with several locales, especially the aura of the frontier in New Zealand and North America, and a sensitivity to the plight of those colonized. After studying at prestigious private schools in England, he sailed in 1936 to New Zealand, where his parents and the previous five generations of his family were from. There he began his painting career as a part-time student at King Edward Technical College in Dunedin. In 1940 he enrolled at Victoria University in Wellington, where he frequented the libraries to study such luminaries as Thomas Hart Benton, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Grant Wood.

Hayman returned to England in 1947. He had his first exhibition later that year at the London Gallery, which largely exhibited Dada and Surrealism. His wordplay and his dreamlike paintings of female nudes, ships at sea, flying machines, long-beaked birds, revolutionary heroes, and (though he was Jewish) Christian stories fit well with Surrealist strategies. In 1953 Gallery One—directed at that time by Victor Musgrave, a champion of “art brut”—held Hayman’s first solo show in London.

Hayman and his wife lived in Cabris Bay, near St. Ives, for several years in the 1950s and 1960s. The landscapes and seascapes, which reminded him of New Zealand, inspired Hayman, as did the artists’ community developing at that time. He befriended artist Peter Lanyon and became more familiar with the work of Cornish artist Alfred Wallis, whom he had read about while in New Zealand. His writings note the influence of the many painted wooden boats in the fishing village on the assemblages Wallis made in the late 1960s. These constructions—built with oil paint, board, nails, and scrap metal—reconcile manufactured forms with organic material to create a unified whole.