Consuelo Amezcua

1903–1975 American, b. Mexico

Tags: Drawing

Consuelo González Amezcua, or Chelo, as she was called, was born in Piedras Negras, Mexico on June 13, 1903, the third child of Jesús González Galván and Julia Amezcua Saenz. The family emigrated from this border town along the Rio Grande River to another, Del Rio, Texas, on Thanksgiving Day, November 27, 1913 when; Chelo was ten years old.

Her parents, both originally from Mexico, were teachers, though Chelo only went to school for six years. Still, she remembered her favorite teachers for the rest of her life. The third eldest child of the family, she had four brothers but was especially close to her sister, Zaré. The family didn’t have much money, but they did share happy times together as their parents would tell stories and, being musically inclined, would play guitar and sing songs for the children.

Portfolio of Work

Click Arrows to View More Artwork

Chelo did have aspirations to go to art school, and in the thirties, wrote to the President of Mexico, Lázaro Cárdenas, asking for a scholarship to attend the Academy of San Carlos. Her request was granted, but the death of her father three days after her acceptance prevented her from attending.

She lived in Del Rio for the rest of her life, working at the local S.H. Kress 5 & 10 Cent store selling candy, but did spend some time traveling in Mexico. Chelo loved to wear intricate filigree jewelry, echoing the motifs found in her artwork. She never married and lived with sister in the family’s home after the death of their mother. On June 23, 1975 Chelo passed away at the age of 72.

Surprisingly, Chelo’s art did not receive much attention from her family, and she recalls that even her sister was discouraging about her poetry.1 Still, she continued on because her art, as well as her poetry and music, was a way to express and celebrate the beauty and spirit she found in all of life.

Drawing Medium and Techniques

Chelo Amezcua did not receive any formal art training, but developed her own unique style and vision. Dr. Jacinto Quirante feels that she is fortunate for not having attended art school. Discussing the potential ramifications, he says:

“Formal art training can sometimes have a debilitating effect on the aspiring artist. Once started on this course he eventually begins to question everything he has done prior to entering art school…All these new experiences obviously affect him. Doubt sets in. All this has to be digested, perhaps forgotten, before he can find his own identity. Throughout this process he gets notions as to what constitutes good and bad art, what is appropriate or inappropriate as far as subject matter is concerned, what are proper or improper materials. All these things Chelo missed.” (2)

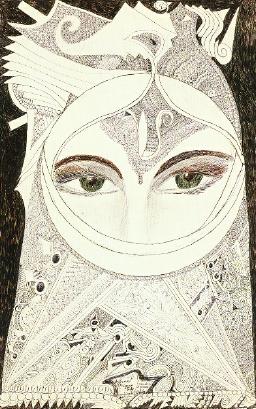

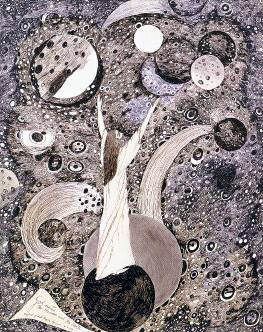

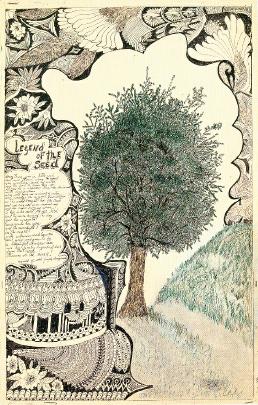

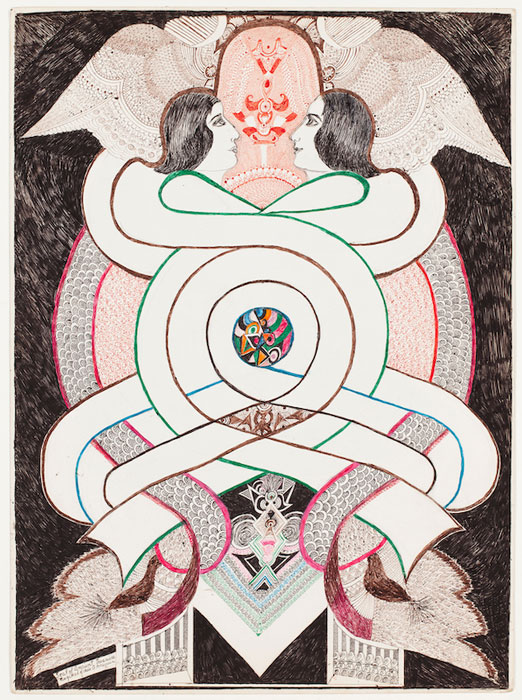

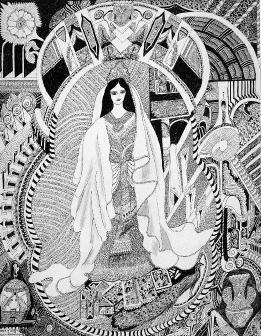

As a self-taught artist, Chelo was completely free to explore traditionally unorthodox drawing mediums and methods. Her preferred tool was a humble ballpoint pen. These suited her artistic vision perfectly – she could produce very fine, intricate, continuous lines without fear of ink running or spilling. A further advantage was that they were plentiful and inexpensive, unlike many artist’s supplies. Later though, she did try working with other types of artist’s inks and pens, but they were not to her liking.

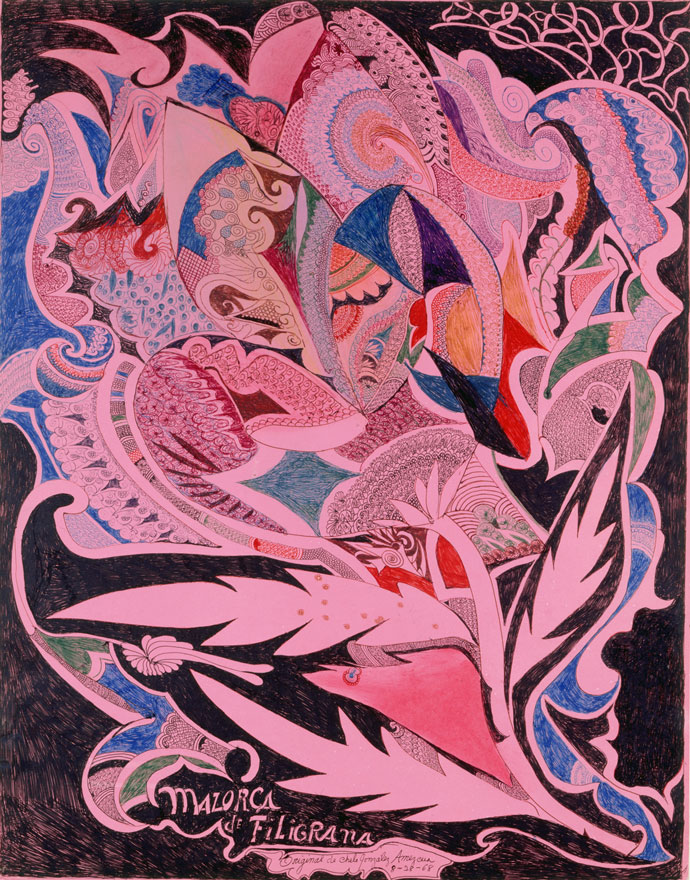

Her early works were done on white card with black pen, and eventually she expanded her palette to include different color inks in her pieces. During the last five years of her life, she added crayon and felt-tip pen to her repertoire, producing even more vivid drawings. Details show that she would also incorporate pencil to provide subtle shading, sometimes with visible strokes, and sometimes blending the marks to make a smooth gradient.

Unlike many artists who prefer to work out their composition through a number of sketches, Chelo would plan in her mind what she wanted the finished page to look like. Once she had a definite image pictured, she would draw the larger forms and figures, then fill in the backgrounds with intricate details and decoration. Her name for her work was “Filigree Art, a new Texas Culture.”

Each drawing took an average of eighteen days to complete, spending three to five hours a day working in the late afternoon and evening. After finishing each drawing, Chelo would turn it over and mediate in a gesture of gratitude for the creativity and the completion of each, sometimes also drawing on the reverse side. She referred to her work as mental recordatorio or “mental drawing,” descriptive of the intuitive and mystic nature of her art.